The character questionnaire for “Whitey’s Boyos” (name still tentative, suggestions welcome) follows. The context: Whitey’s squad of demon-killing hard-nosed bruisers has around for nine months or so now. A couple of the original members have died; there have been a couple of new recruits. The player characters are the entire squad. They are not expected to have jobs outside the life — Whitey pays a generous stipend to people willing to risk their lives fighting demons.

Some of the questions can’t be answered until all the characters are in, and since the final roster hasn’t been finalized, that’s obviously a little ways away. This is mostly so I get it written down and have time to chew on it.

The questionnaire is written in the masculine gender. This doesn’t mean that female characters are impossible, but after deliberation, I think the gender choices in the language reinforce the fact that female characters would exist within a sexist environment.

1. Who does your character hate? Who screwed him over? Who would he hurt, given a chance?

2. Which family member is your character closest to? (Yes, your character has a living family member.) What’s the relationship like?

3. Which member of the squad saved your life? Which squad member’s life did you save? How’d it happen? Can’t be the same person.

4. Where does your character hang out? Where does he feel safe? Where does he go to relax?

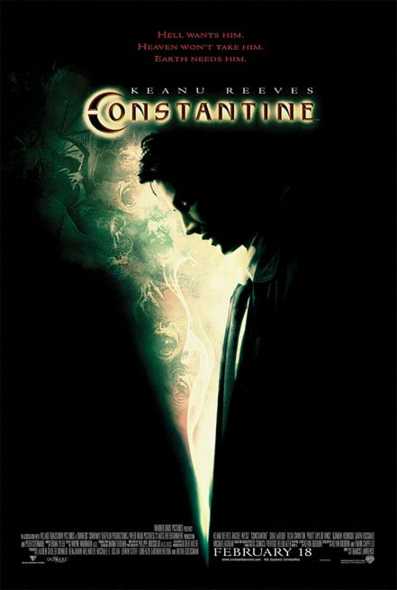

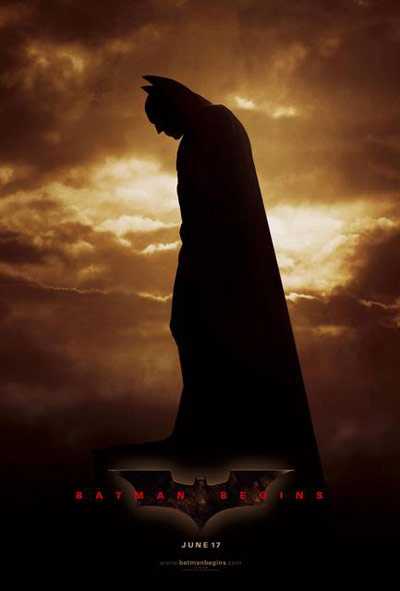

5. What’s your character’s favorite movie? Favorite album?

6. Does your character go to Mass? If not, any other regular religious activity? If not, why?

7. What would your character’s perfect evening be like?

8. Who is your character dating and/or sleeping with?

9. What would your character do with a million dollars? How about a hundred thousand?

10. What’s the worst disappointment of your character’s life? What’s his greatest achievement, from his point of view?